Imagine a healthcare system where compassion and care are valued equally.

Problem Statement

Healthcare professionals (HCPs) need to “see” and treat the patient - not just the illness. Effective treatment and care combined with compassion and empathy lead to better health outcomes (Sinclair, Norris, McConnell et al. 2016). A more holistic approach is therefore needed in healthcare; one that considers the patient, the caregiver and the HCP all as human beings with complex needs and circumstances. This should be inherent in the daily work of HCPs, as it is often missing as described, for example, by Haslam (2015): “[c]ompassion is not an optional extra, but far too frequently it is seen as being much less important than other aspects of care”.

Discussion Summary

The human rights perspective

A human rights approach to health is strongly believed in and endorsed. This Position Paper has been developed with the main objectives of equality and equity with a strong call to all stakeholders to respect human rights, specifically the right to health.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UN, 2015) states that “[e]veryone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of him/her and of his/her family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services…”.

The right to health is an inclusive one composed of different aspects that include freedom from discrimination and the right to health-related education among others.

The right for people to receive the healthcare services they need, when and where they need them, without experiencing financial hardship, referred to as universal health coverage below, also depends on patients taking a proactive role in their individual health. By assuming more responsibility for self-care, and engaging actively in preventative measures, patients can significantly reduce the burden on healthcare systems.

Findings from the IEEPO global patient survey demonstrated a clear ask for universal health coverage.

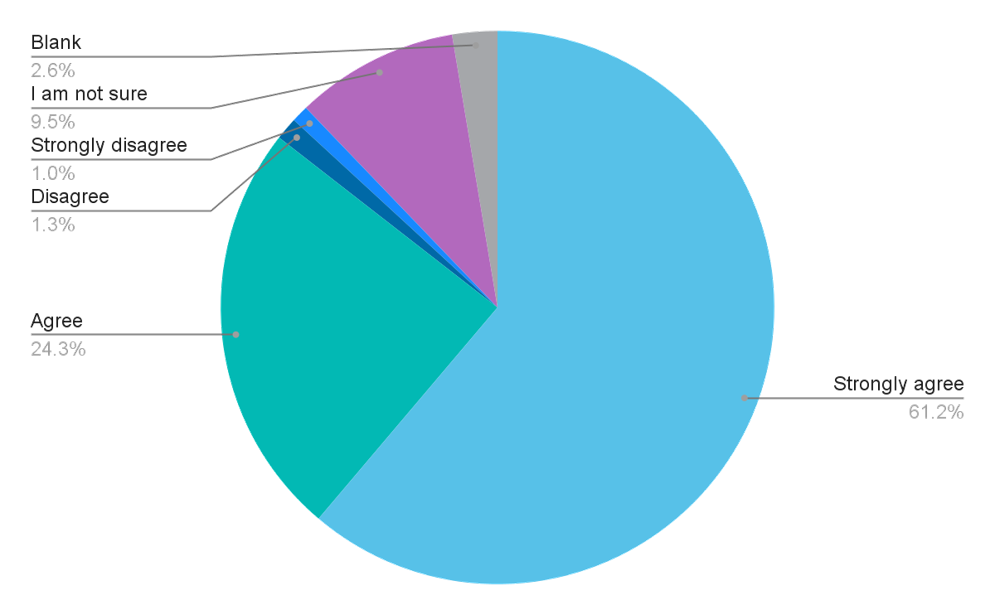

85.5% of the respondents agreed or strongly agreed that universal health coverage should be the goal when governments are investing in health. At the same time, the survey results also demonstrate that this is not happening to a satisfactory level everywhere.

To what extent do you agree with this statement: ‘Universal health coverage (UHC) should be the goal when governments are investing in health, to provide health services people need without financial hardship’?

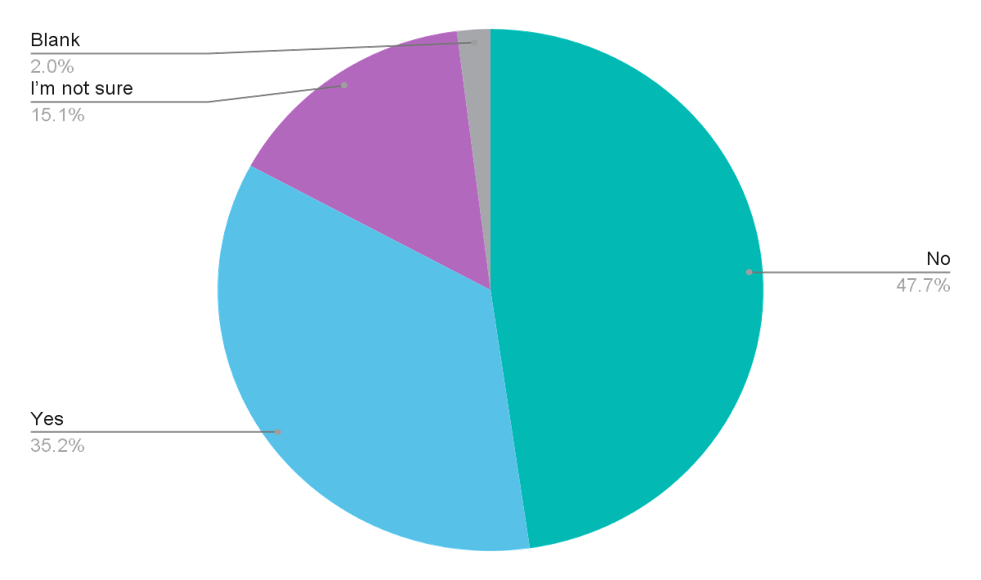

When asked about the availability of universal health coverage in their countries, 47.7% of the respondents said it did not exist, while 15.1% were not sure. Not being sure if there is universal health coverage for the people who need it is more indicative of it not being available.

There is acknowledgement that healthcare systems across many different countries may have more pressing priorities, especially after the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the principles of fairness, equity and humanisation should underpin all stages of the evolution of healthcare systems.

The term compassion is defined as sensitivity shown in order to understand another person's suffering, combined with a willingness to help and to promote the wellbeing of that person in order to find a solution to their situation.2

Human beings are emotional creatures, and our emotions interact with and directly impact our physical health. Compassionate care that is sensitive and respectful of a person’s pain as well as their emotional state can therefore transform health service delivery and lead to improved patient health outcomes.

Compassion also needs to be extended to healthcare professionals. Overburdened even before COVID-19, the situation has worsened considerably during the pandemic with 50% of HCPs reporting burnout, according to a global study (Morgantini, Naha, Wang et al. 2020). Overburdening makes it even more difficult for healthcare professionals to find the time needed to provide the compassionate care that their patients need. This in turn can lead to a lack of trust and rapport between patients and HCPs that undermines entire healthcare systems. Compassion should not be an optional extra, however, far too frequently it is seen as being much less important than other aspects of care.

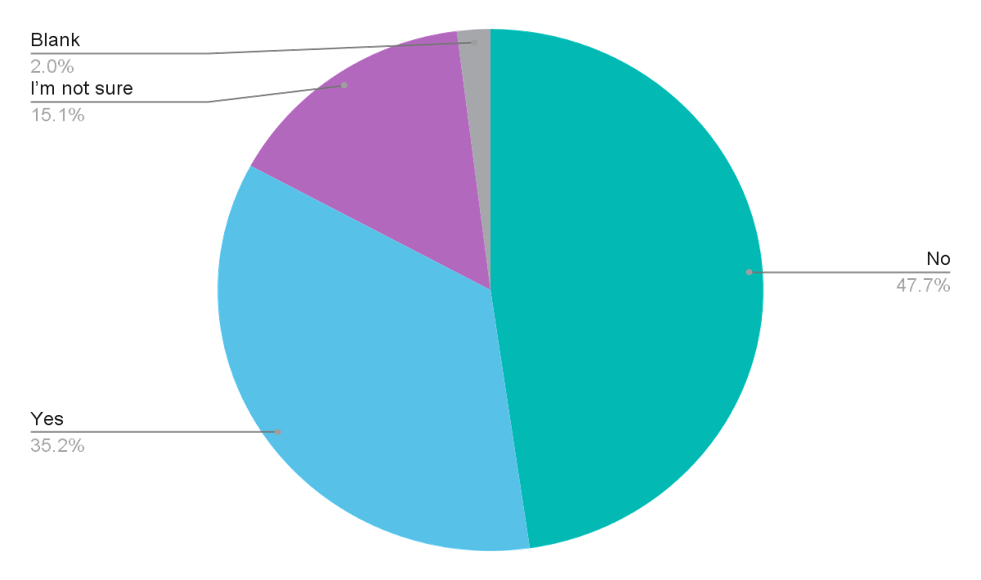

The IEEPO global community survey demonstrated that there are considerable shortcomings when it comes to the provision of compassionate healthcare.

37.5% of the respondents said that individual patients' needs are not recognised or treated with compassion in their country. Another 22.7% said they were not sure if this was the case, suggesting that even if there is compassionate care, it is not sufficiently visible.

To what extent do you agree with this statement: “Individual patients' needs are recognised and are treated with compassion by the healthcare providers in my country.”

When asked specifically about compassionate care, respondents indicated three main challenges:

- Insufficient resources

- Largely dependent upon the personal attitudes and mindsets of healthcare professionals

- Lack of digital tools that could streamline healthcare and improve efficiency, thus freeing up time and resources for compassionate care.

Paradigm change

Transforming healthcare into a more compassionate and humanised system requires a paradigm change. Instead of focusing on symptoms and illnesses, focus needs to be shifted to the people affected by them, acknowledging that the lives of patients, their caregivers and families are often profoundly changed or affected by an illness.

A more humanised and compassionate healthcare system also relies on listening to each other more. Improved listening skills will help further understanding, inform better joint decision-making and support co-creation of solutions and/or initiatives leading to better outcomes that matter to patients.

Improving health literacy to support self-care and empowering patients to take a more proactive role in managing their own health, also underpins this paradigm shift. The specific challenges in health literacy, and some suggested solutions are discussed in the chapter “Humanising health literacy”.

The evolution in data technology needs to be managed to help ensure healthcare becomes more humanised (as opposed to automated) and respectful of the diverse needs and circumstances of people. The chapter “Humanising digital healthcare to build capacity by harnessing the power of patient data” offers further insight and concrete proposals on how this could be achieved.

The International Alliance of Patient Organisations (IAPO)3 has also identified the five key elements of patient-centred healthcare:

- Respect for everybody

- Empowerment and choice of preferences in healthcare services

- Participation and engagement in the healthcare system for patients on all levels and points as they know best what they need

- Information: the healthcare system should provide relevant and accessible information for all patients

- Support and service: a more holistic approach is needed.

Respect for all is prioritised as it is the fundamental requirement for humanised and compassionate healthcare. It is also one of the most important recommendations of this Position Paper.

Doing it together

The views and perspectives of patients still need greater legitimacy; and the institutional framework for authoritative patient involvement and co-creation is still missing.

Patient organisations should participate in and be better integrated into the medical education of healthcare providers in order to provide the patient perspective early on in their careers. Over time, a more empathetic and humanised approach to healthcare can emerge if all professions involved in healthcare service delivery learn how to work with patients, i.e. co-create with patients. Conversely, the conscious integration of patients (and their organisations) into medical education will further educate patient communities about the particular problems and challenges faced in healthcare.

Building upon IAPO’s five key elements of patient-centred care, it is essential that patients are able to work efficiently within the health policy arena. More direct contacts and structured exchange between policymakers and patient communities should be built.

The chapter “Humanising health literacy” discusses the importance of self-care and the acknowledgment of traditional knowledge in health. These objectives also call for increased and enhanced cooperation with stakeholders in healthcare beyond the pharmaceutical industry and healthcare professionals. At the same time, it is imperative that patients and healthcare professionals build a stronger two-way rapport with each other. It is encouraged that doctors and nurses listen and really hear and understand their patients’ needs; and likewise for patients to understand the pressures that the medical professions are also under as they try to help them. The need to strengthen partnerships between people with illnesses and healthcare professionals is critical. This process is not about demanding patient rights, it is about the exchange of solid and helpful information in order to support informed decision-making and better holistic care including self-care.

Last but not least, the continuation of meaningful and sensitive conversations across the broader industry including biopharmaceuticals, medical device manufacturers and pharmaceuticals is crucial. Despite this being a highly politicised and often conflict-ridden field, strong working relationships between the pharmaceutical industry and patient communities are essential and productive. Some describe this relationship as parasitical on both sides. In fact, it is a symbiotic relationship that creates mutual value for patients and society throughout healthcare systems: all stakeholders (and the state as well) need each other to thrive (Bereczky 2019).

Case Study: Australia's National Oncology Alliance

Project background and objective

National Oncology Alliance (NOA) is a coalition of cancer stakeholders founded by Rare Cancers Australia, bringing together patient organisations, patients, clinicians, and industry. Roche was one of several founding supporters of the alliance. NOA is co chaired by Rare Cancers Australia Chief Executive Richard Vines and Director of Cancer Medicine at Melbourne’s Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre, Prof John Zalcberg. The cancer community in Australia is fragmented, with different stakeholders often working in isolation to develop strategies to improve cancer care. This piecemeal approach risks not being able to realise the full promise of new science and emerging health technologies. NOA set out to work collaboratively across the cancer community to co create a proposed 10 year national plan for cancer care in Australia. The aim was to bypass the entrenched positions and status quo and capitalise on the opportunities presented by emerging health technologies.

Activity detail and stakeholders involved.

NOA began by issuing a discussion paper making the case for a new 10 year national plan for cancer care, followed by a series of 12 virtual workshops with a range of experts to discuss emerging therapies, patient centred car e, AI and big data, genomics, clinical trials etc. Over 1,000 people attended, with an average of 85 per session, which formed the basis of the final Vision 20 30 report. The report articulates the future of cancer and identifies elements of the health system that will require change if patients are to achieve the best possible outcomes as treatments evolve and emerge over the next decade. The report was presented to the Minister for Health days before its public launch at Rare Cancers Australia’s annual policy conference CanForum, which was attended by more than 1,000 stakeholders and opened by the Minister, who endorsed the report.

Activity outputs and outcomes

The Minister has referred the report to Australia’s peak government cancer control agency Cancer Australia and asked them to implement it. Cancer Australia’s CEO is due to provide a progress update at Rare Cancers Australia's annual cancer congress in November 2021.

Further information: https://www.rarecancers.org.au/page/143/vision-20-30

Calls to action

1. Patient organisations should facilitate conversations with all stakeholders about the need and value of compassionate care.

2. Create a Global Compassionate Care Charter in partnership with healthcare professionals, the patient community, and policymakers to educate on the integral, evidence-based value of compassion in healthcare, and gain support from policymakers and other stakeholders. Resources and tools need to be developed to support the creation of the Charter.

3. Bringing patients, caregivers, healthcare professionals, and other ecosystem stakeholders closer together so that they can listen to each other and understand different perspectives is key. One way of achieving this is to allow patients to participate in the medical and scientific conferences. This idea is explored further in the chapter: “Humanising health literacy”.

4. Established patient communities should help develop patient organisations in resource-constrained countries to help ensure the global reach and education of all stakeholders.

Link has been copied to clipboard