Imagine a healthcare system that respects diversity and treats everybody as equal.

Chapter 5 Ranjt

Problem Statement

Diversity, equity and inclusion must be central to humanising healthcare systems and ensuring patients are treated as individuals that share the same biology and essential humanity, despite their diversity.

Discussion Summary

The international survey performed by IEEPO asked participants about their views on equity and inclusion in their healthcare systems.

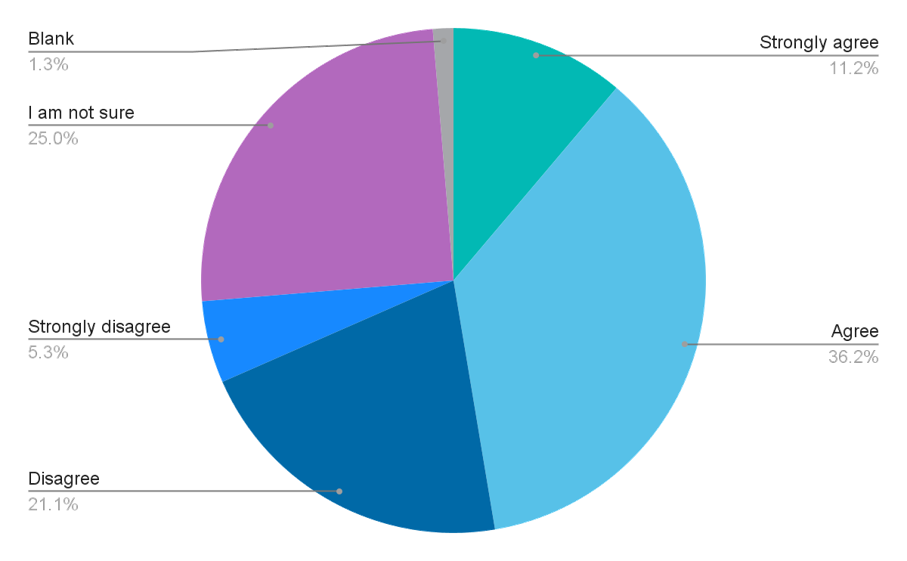

To what extent do you agree with this statement? “The healthcare system in my country is working to decrease the unfair and avoidable health differences (access, resources and outcomes) people may face because of race, religion, gender, disability, age, sexual orientation and socio-economic background”

The answers show a mixed picture. Most of the respondents (47.4%) agree or agree strongly with the statement that their healthcare systems work to decrease differences based on discrimination. 26.4% disagree with this statement, however 25.0% are unsure

A broad and sensitive use of the term diversity should be instilled, which encompasses certain domains that appear to be less obvious in the conversation around equity and inclusion: Greater attention should be paid to how healthcare systems can be strengthened to serve all patients, regardless of socio-economic background, country healthcare infrastructure, location, language or any other societal and personal circumstances. This should be factored into patient interactions and experience, and co-creation at every step in the holistic healthcare journey, from prevention to diagnosis, treatment, and survivorship.

Diversity includes differences across the following areas:

- Inequalities in access to health according to ethnic background

- Differences between urban and rural areas, and other geographical inequities (e.g., distance from medical centres)

- Differences affecting nomadic communities

- Differences on the basis of educational background

- Linguistic diversity

- Differences on the basis of literacy

- Different health challenges resulting from migration

The need for a broader and more inclusive definition of diversity is associated with the growth in migration trends across the globe. The resulting variety in cultures and socio-economic status calls for more sensitivity towards different needs and circumstances.

Diversity, equity and inclusion are key to ensuring innovation (Hewlett, Marshall and Sherbin 2013). When differing perspectives are embraced and represented, there are more opportunities to co-create new and surprising solutions. When personalised healthcare or precision medicine are mentioned as an important emerging trend in healthcare and health related research (Obama 2015), this encourages increased respect for the needs, genomic setup and circumstances of individuals and their communities. Personalised healthcare cannot become a privilege contributing to more inequality. Poverty and extreme poverty are still often a reason for discrimination and stigma.

Discussing inclusiveness and the reduction of discrimination also calls for an open conversation about biases and prejudices in healthcare, research and development. An article in The Scientific American12 admits that racial and ethnic diversity is underrepresented in clinical trials. These affect not only patients and citizens but also healthcare professionals. Doctors, nurses and healthcare service personnel are also diverse and represent different socio-cultural backgrounds. Information and education about diversity and inclusion must go both ways. Wilbur, Snyder, Essary et al. (2020) assert that “A diverse healthcare workforce is necessary as a means to help care for an increasingly diverse patient population”.

The role of language

Acknowledging diversity in language means more than reflecting and respecting linguistic diversity. As previously discussed in the chapter on “Humanising Health Literacy”, there is also a language barrier between the medical profession, policymakers, and patients. This language barrier also creates power imbalances as described by Galjour, Schwarz, Rusike et al. (2021). While most people understand basic information about their bodies, health and illnesses, the language of health can be very different across different stakeholders. The use of language also extends to making sure that healthcare professionals avoid judgmental language, while their demeanour remains respectful of the patient.

Patient organisations are, however, in an excellent position to manage this difference. They can not only translate medical language into lay terms through brochures, websites, social media and lay language summaries, but they can also convey lay concepts about health in scientific and medical terms. In addition, the importance of arts (theatre, song, dance, visual arts, storytelling, etc.) in health promotion and health literacy is well documented (e.g., Bunn, Kalinga, Mtema et al. 2020). Patient-led research is thus a key tool for the acknowledgement of diversity and the elimination of discrimination whilst also helping tackle stigma against low-educated people and those living in poverty. This fundamental challenge is discussed further in the chapter “Humanising health literacy”. McCorkell, Assaf, Davis et al. (2021) describes the importance of patient-led research in the field of Long COVID and find that “[p]eople experiencing the illness are best able to identify the questions to ask and issues to investigate that matter to them and also to design effective solutions based on their intimate familiarity of the illness”. Another key issue is trust: Heath (2019) points out that “[d]elivering care in the language with which the patient feels most comfortable, creating a positive and non-judgmental environment, and being honest with patients will be key to creating trust”.

When talking about language, one should cast a wider net than to just focus on linguistic diversity and the need for translations. The bulk of scientific and medical literature is in English, which poses a problem on two levels:

1. Patients who don’t speak English, or don’t speak it well, cannot access important and potentially life-saving information unless translations are produced (Woolston, Osório 2019)

2. Scientific and medical literature produced in languages other than English tend to fall off the map of science (Huttner-Koros 2015).

Knowledge is empowering

Keeping community members alive and healthy is an instinctive commandment that transcends history and cultures. There is, however, considerable conflict between what is acknowledged as evidence-based medicine, and what is seen as traditional, alternative or complementary medicine. There must be a clear line between real and fake medicine - and this distinction should be maintained in the interest of real health improvements globally. The growth of anti-science movements in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic is a warning sign that there is an urgent need for better health literacy.

The importance and empowering aspects of learning and knowledge have been described in the literature of patient involvement several times (Epstein, 1995; Bereczky, 2020). Knowledge is also fundamental in tackling stigma and discrimination as it is common for humans to fear and loath what is not known well enough (Carleton, 2011). The case study of the U=U Campaign (Undetectable means Untransmittable) in the HIV field provides a good example on how the dissemination of a fundamental piece of scientific knowledge can contribute to the reduction of stigma and discrimination. The aspect of co-creation and joint delivery with patient communities play a major role in these efforts.

Taking the message to the people

Effective outreach work that includes targeted efforts to address specific groups is key. Sometimes, “hard-to-reach” populations are not hard to reach, a different approach needs to be tested. Taking the first step towards disempowered groups is the first step towards reducing inequality resulting from discrimination. Even if certain populations cannot find the way to access healthcare services or don’t know how to navigate the system, all stakeholders can still move towards them and bring these services closer to them. Therefore, in the calls to action, all stakeholders should reach out to underserved populations and to examine their own biases that may act as barriers to access to health. The principle of “meeting patients where they are” (and not where you want them to be) was already described by Hughes in 2013 and has become imperative when talking about reaching vulnerable populations. The IEEPO global community survey also provides further insight into this issue.

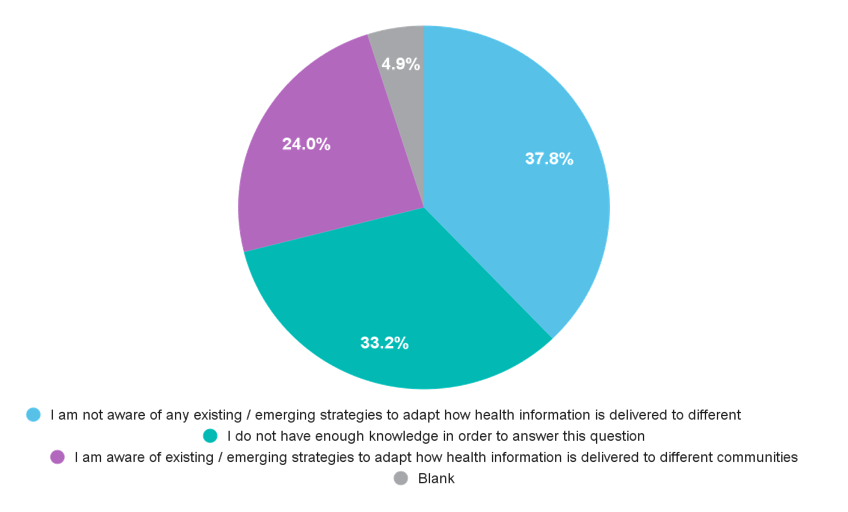

In your country / region is there a strategy to adapt the way health service delivery and information is made available to different communities (incl. underserved, marginalized groups), depending on their situation and how they access information? For example, rural communities who are isolated may not receive timely information about updated treatment regimens or timely access to digital tools / technologies.

Case Study: Undetectable means Untransmittable

Project background and objective

The U=U Campaign is a global example about how the dissemination of a fundamental piece of scientific knowledge can amplify a powerful public health message. It is also an example of how partnership working between healthcare professionals and patient communities can play a major role in changing peoples’ behaviour, improve health outcomes and lead to a reduction in stigma and discrimination.

In recent years, an overwhelming body of clinical evidence has firmly established the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) Undetectable = Untransmittable (U=U) concept as scientifically sound. U=U means that people living with HIV who achieve and maintain an undetectable viral load (the amount of HIV in the blood) by taking and adhering to antiretroviral therapy (ART) as prescribed cannot sexually transmit the virus to others. Evidence for U=U was developed over many years of research, col laboration and study including observational studies, expert opinion based on reviewing evidence, prospective observational studies, randomised clinical trials and further expert opinion in 2016 which led to the development of the U=U campaign.

Distilling the message into a single, powerful and meaningful statement “U=U” was intended to promote prevention at all levels, including primary (preventing transmission to uninfected persons) and secondary (ensuring regular viral load monitoring and health screenings).

By focusing on being ‘undetectable’, an objectively measured health indicator, U=U provides people living with HIV with an unambiguous health target that emphasises personal responsibility and the importance of reliable and affordable access to medicines and diagnostics.

Activity detail and stakeholders involved

Launched by the community of people living with HIV in 2017, U=U became an international campaign aimed at raising awareness of prevention. By January 2021, more than 1000 organisations fr om 102 countries had signed up, including international bodies and medical associations. More specifically, the U=U message has also been incorporated into clinical guidance. Discussing U=U in clinical settings is vital because patients are more likely to believe information that they hear directly from their peers living with HIV in addition to healthcare providers or doctors. In May 2019, these results were published in The Lancet, and became one of the most widely and rapidly reported interna tional headline HIV news in mainstream media.

Further information: https://www.preventionaccess.org/

Calls to action

1. All stakeholders should focus on the humanising of healthcare and how the person in need can become the point of gravity of their work.

2. All stakeholders should ensure that there is representativeness in their work, become a more diverse team at every level, and look at their constituencies critically. Representativeness means the inclusion of all affected populations regardless of their socio-economic, ethnic or other backgrounds. All stakeholders should strive to be aware of their own biases and identify them to be able to tackle them. Self-critical engagement with biases and prejudice will lead to more inclusion and sensitivity to the challenges of underserved populations.

3. Sensitivity to language as a tool for building trustful relationships should be developed consciously in all stakeholders including policymakers, healthcare professionals, researchers, and patient organisations.

4. Science and educational systems need to acknowledge the importance of diversity and inclusion. Early inclusion training will result in better anti-discriminatory practices throughout the entire healthcare continuum. Researchers and the clinical profession should include “real” instead of “ideal” patients in clinical trials to make sure that outcomes are more meaningful and those in need are served better.

Link has been copied to clipboard